Up to this point, I've been critiquing the ITDP's Boston bus rapid transit report. That:

I think that about sums it up. If you need a tl;dr, see the picture to the right. What this and the subsequent post will focus on is where and how Boston can improve it's buses, and where bus rapid transit is, and is not, the best technology to use. We'll look at street widths, capacity constraints, growth potential and system integration, several factors the ITDP glosses over in their "lines on a map" "analysis." Here are, more specifically, the factors I'm using to analyze these routes:

With that said, let's look at some areas that could benefit from better transit in Boston. I am going to break this in to two posts to keep it from getting too long: one examining the ITDP study corridors, and another other corridors which I think might have a better return on investment for bus improvements.

Let's examine these in a bit more detail. In the interest of brevity (ha!) we'll start with the ITDP's corridors and cover the others in a subsequent post.

Silver Line, downtown to Mattapan; Washington Street and Blue Hill Avenue. This is broken in to two routes in the ITDP study, but really they combine as one. And this is an incredibly important transit corridor, linking a huge swath of lower income neighborhoods in Boston in with the downtown core. Better transit would serve these communities well, and increase transit-accessible housing in the region dramatically. This is important in curbing gentrification by dramatically increasing supply so that demand, latent and induced, can keep pace.

And this is a good candidate for bus rapid transit! South of Warren Street, Blue Hill Avenue is more than wide enough for a high-quality BRT system. North of there, there are constrained sections, but only a couple of major bottlenecks (Warren Street, just north of Dudley Square). But there are two major issues with bus rapid transit on the corridor. First, it might hit capacity, like the Orange Line in LA has. Without grade separation or passing lanes (neither of which are feasible, especially in the more heavily-used northern portion of the line) better-than-three minute headways are difficult without without bunching and load balancing issues. And with narrow roads downtown, even 60 foot buses are a stretch, longer buses would be difficult even if they were used in the US.

Second, downtown. Boston had a problem with surface transit clogging downtown 120 years ago. We solved it by putting transit underground. I'm

very on the record as saying that buses are a good thing in downtown Boston. But with narrow streets and limited terminal space, downtown Boston doesn't need more buses, especially buses which need to maintain even headways in both directions; most of the current routes are express buses which carry few people on their outbound trips; others mostly use the already-busy Haymarket busway. (I've

written ad nauseum about the perils of scheduling a busy route without recovery time at both ends.) We certainly shouldn't banish the buses we have, but we also should be wary of too many more.

What makes sense for this corridor is light rail. It can also deal with a few short street-running segments (although the ITDP would believe otherwise: see page 22

here where they sell BRT because it can run in mixed traffic while light rail cannot; this is patently untrue) and has higher capacity. But the major advantage is that instead of threading through narrow downtown streets, light rail can use existing infrastructure and use the subway along Tremont Street to reach Government Center and beyond. As someone commented to me, we solved the issue of running transit on downtown streets 120 years ago. Well, more like

118.

Is there capacity in the subway? West of Boylston, there is not. But from Boylston to Park Street, there are four tracks, and the inner two tracks which come in from the west are separate from the outer two tracks, with a turning loop to send cars back. So by terminating some cars at peak hour at Park Street, it would open capacity to have cars from the now-abandoned

Pleasant Street incline in their slots. This might mean, at rush hour, turning B cars at Park Street. Some B Line riders might have to make a cross-platform connection to high-frequency through cars for the trip to Government Center (where they terminate today), but it's a small price to pay for proper underground service.

And if you do that, you don't have to try to engineer BRT on to narrow downtown streets where it doesn't belong. In Mexico City, Line 4 is the only section on similarly narrow streets, and those streets have no vehicular access to businesses, something that would be difficult to implement as most streets in Boston require deliveries made by vehicle. Even so, that line in Mexico can only run 40 foot buses, platforms have few of the amenities associated with BRT (there's nowhere to put them) and capacity is constrained. The report's "

technical analysis" spends a lot of time examining how to route BRT downtown by completely taking over streets, which is basically a non-starter. I'm not sure how businesses in the Centro Histórico are serviced (parallel streets, perhaps) but for most areas of downtown Boston, there needs to be at least some vehicular access to the streets, especially since the Centro Histórico is more akin to the North End than the Financial District. In any case, this is probably a nonstarter on downtown streets in Boston.

Yet the cost of rebuilding the Pleasant Street incline is certainly not inexpensive. Both downtown solution are costly, yet one only integrates with existing light rail capacity and another only with BRT. Perhaps the solution downtown, right now, is to do the minimum. Run buses on the Silver Line route, perhaps with better lane priority, but don't try to carve out BRT through the Financial District for a high cost and low return.

And south of that point? Do everything. Build a true light rail-ready BRT corridor. In name, San Francisco is doing this on Geary, but conversion would still require the removal of concrete and the installation of electric capacity, both of which would be disruptive to transit operations for some time. If you are going to completely rebuild the street (which either mode would require) put in the disruptive infrastructure for the future. The marginal cost of setting rails in concrete is minimal (and some portions would be used by buses even if light rail trains ran as well), and if you're already digging down, building the necessary electrical conduit system costs a lot less (substations can be added later). Then, if and when money becomes available for the Pleasant Street incline (which may dovetail with capacity constraints), you can easily convert the corridor to light rail operations without digging up your investment.

It's also more of a commitment to the community. One of the reasons (I believe) the

28X proposal was sunk is that it was an inferior product in the neighborhood without any promise that it would ever be comparable to rail service. The current study does little to quell those fears, especially since the Silver Line is often full and the bus lanes it uses disappear where they're needed most downtown. The

2012 study of modes that made the curious assumption that a light rail line with one-seat rides downtown would actually decrease transit use was further "proof" to community activists that the deck was stacked against rail transit. (This may be due to fewer transferring passengers, so there would be more overall journeys, but fewer unlinked trips. Of course, this is coming from an agency which

defines highway capacity by the number of vehicles moved per hour, not the number of people (!) so take it with a grain of salt.) And proposals for limited-stop buses along the 28 (from the same study) still don't promise a one-seat ride downtown, although at rush hour, considering the chance of getting a seat on the Orange Line at Ruggles, it might be a good descriptor.

Building a light-rail ready line, and actually putting some track in the ground, would be a commitment that, yes, the goal is a system which integrates with the rest of the transit network. The fact that there is spare capacity in to Park Street is icing on the cake. For much of the T, getting more capacity would require major track and signal upgrades. But the tracks at Boylston are there, and the quad-track running in to Park could allow for additional service.

Yes, this will cost somewhat more. But light rail doesn't cost

that much more than bus rapid transit, and if you don't string wire, add substations or buy vehicles, it pulls the cost down further. Steel rails only cost so much. But you won't be stuck in a Orange Line-esque sunk cost conundrum like in LA. There, the initial cost to build BRT plus the cost to upgrade it is nearly the cost of tearing it out and putting LRT in it's place. It's a sunk cost white elephant. Don't build that here.

|

Neighborhood street with no parking

or bicycling facility. Also, no room for

a bus station. Yup, this makes sense. |

Hyde Park to Forest Hills (32 bus). Here's a line appropriate for BRT … if the street was wider. As it is, there would be enough room on much of the corridor for BRT, travel lanes and, well, that's it. If there were a parallel street for, say, bike lanes, that might work, but there's not. Hyde Park Ave is the main artery through the neighborhood, and it needs to be a complete street. The ITDP's proposals leave enough room for one travel lane, or require one-way splits which are

poor transit planning, especially if there's a barrier (the Providence Line) in between. There is also no plan showing how to fit a bus stop in to to these narrow areas. Presumably everyone will walk a mile to wider parts of the street as empty buses roll through?

Then there are other users. There is, apparently, no need to have provisions for cyclists in Hyde Park Ave. We often talk about making streets more comfortable for cyclists, and a single travel lane shared with cars is certainly not a high level of comfort. This is also not somewhere where bike/bus lanes make sense, as buses would be slowed by passing cyclists more than they are in traffic (more on this later; in some short segments they do make sense). So to speed buses, all cyclists will either have to poach bus lanes, risk narrow travel lanes with no shoulders, or take a circuitous route. More likely, they just won't bike. And let's talk about parking. This is a neighborhood street. It would be great to give people a BRT option, but you can't build a street with zero parking. Not just politically. At all.

Is what is proposed even gold standard? Not even close. By the ITDP's

own standards, I doubt this corridor would score higher than the bronze level. Would the 32 benefit from stop consolidation, proof-of-payment fare collection, better stop amenities and bus lanes on the wider part of the corridor? Certainly. Again, to make an analogy to the Twin Cities, this is exactly what they're doing with the 84 bus on Snelling. Fewer stops, better amenities, off-board fare collection. Costs a lot less, gets most of the benefits. Perhaps those are the steps to take, not pushing through a politically unpalatable busway which will anger drivers, cyclists and pedestrians, and which won't have much marginal benefit.

Dudley to Longwood and Harvard/Sullivan. Like the Downtown-Dudley-Mattapan corridor, this is one of the most important corridors in the city. It links several transit lines with major employment centers, both current (Longwood, Kendall, Harvard) and upcoming or potential (Sullivan, Dudley, and nearly Assembly). But there are no wide roads between them, and the roads that do exist have numerous pinchpoints and bottlenecks. Constructing bus rapid transit would be a massive undertaking (The urban ring proposal was for a mile-long tunnel below the Longwood area,

perceived as "the rich get their tunnel and the poor get pollution." If you're going to build a tunnel, as we've seen with the Silver Line, don't hamstring it with low capacity bus service.) and still would be serving as a major crosstown and last-mile route with high and imbalanced peak transfer loads, resulting in a system unable to cope with capacity.

It has two potential outcomes which the Silver Line illustrates well:

- The SL4/SL5 scenario. A watered down BRT that will fail to deliver the promised time savings. This has happened on the SL4/5 from Dudley to Boston. It doesn't have enough signal priority, street width, or enough priority in congested areas (where it really needs it) and is barely faster than the bus lines it replaces (the CT2 and others). It hobbles along with relatively strong ridership, but never really attracts new riders or takes pressure off the downtown subways or achieves the time savings to attract new riders who currently drive. This is the far more likely scenario. It is notable that even the ITDP's rosy predictions for this route offer only modest time savings.

- The SL1/SL2 scenario. There is money and political will to build a proper BRT system: full signal preemption, elevated platforms, 60 foot buses, significant grade separations, the whole nine yards. We don't have the street width for passing lanes, so the system is run as a single line. There are quickly diminishing returns once you start running more than 20 buses per hour per direction and it's very unlikely that you can get beyond 30 buses (one every two minutes): minor fluctuations in passenger loading will quickly cause bunching. Considering that the corridor acts as a last mile transit line for several major subway and commuter rail lines, this is all but inevitable.

So you get a white elephant: spending a lot of money (the SL1/2 cost $625m in 2004, equivalent to $800m today, or about half the cost of the GLX, with much lower throughput) and quickly go over capacity with no way to add more. The 32 buses hourly in the Silver Line waterfront tunnel have a theoretical crush capacity of 3,200 passengers (less, actually, given the luggage racks in the SL1, and bunching and delays as the buses can't handle influxes of transfers at South Station). This is significantly less capacity than a single branch of the Green Line (which could be more efficient with fare pre-payment and signal priority), and less than a quarter of the combined capacity of the Green Line central subway, which, with 37 trains per hour carries more than 12,000 passengers. If the Green Line ran all three-car trains, it would have six to eight times the capacity of a BRT line.

This is particularly worrisome for these corridors because they have the potential to be a major last-mile collector system between Commuter Rail lines and employment centers, driving mode shift beyond the corridor itself. If you build an urban corridor and move 1000 people from driving 5 miles to riding a bus five miles, you save 5000 vehicle miles traveled each day. If that same corridor also serves as a good last mile connection for 1000 employees who each live 20 miles away, you quintuple the congestion and air quality mitigation, not to mention getting more people on commuter rail corridors, most of which have some excess capacity. But it has to be fast.

Right now, passengers from any Southwest Corridor line (Needham, Franklin, Providence) or the Worcester line have to go downtown and transfer to the Red Line to get to Harvard or Kendall; passengers from the north have to change to the Orange or Green lines at North Station to get to the LMA, all of them crowding the downtown subway system. Worcester passengers pass within a mile of Harvard Square and Kendall, but have to travel all the way downtown and then backtrack on the Red Line through downtown to get to work. Even LMA workers have to get off at Yawkey; at least it's a short bus ride—or walk, even—from there. Thus, many drive, because these last mile connections take a lot of time and make transit less time-competitive.

Even if there were more frequent, direct buses, they still would sit in gridlock on the BU Bridge (for the CT2) or Mass Ave to make these connections (and the Boston BRT report points out that there's really no room on the BU Bridge for BRT; the Harvard Bridge might be a different story). For a worker coming to Kendall from Framingham, the fastest option might be to get off the train at Yawkey and walk. But this is not a great solution, nor attainable for everyone (especially given fickle Boston weather, we're not all #weatherproof).

What these areas need is better grade-separated, high-capacity transit service. Yes, rail lines. The first is obvious: from the proposed West Station in Allston along the Grand Junction. MassDOT proposes DMUs, although for a corridor of this length it would make more sense to put up wires and run EMUs or integrate with the existing light rail infrastructure (and, perhaps, tunnel through Cambridge, which would increase the cost, capacity, utility and land values above-ground). Commuting from west of Boston to Kendall Square is a black hole for transit: taking transit requires 25 to 30 minutes just to get back to where you started from; surveys frequently show much lower transit commute percentages from western suburbs than other areas in the region. A good connection from Cambridge could shave 30-45 minutes off the transit commute daily, and there's plenty of capacity on the Worcester Line for those commuters. It could also catalyze development with a station in Cambridgeport, which is currently a compendium of empty lots, parking lots and low-slung buildings.

But the real meat is in where it could be extended. First, an extension of some service to North Station would provide better service between north side commuter lines and Kendall (full disclosure: I work for the Charles River TMA, which operates the EZRide Shuttle between North Station and Kendall and is too often hamstrung by traffic delays; these opinions are my own), the Worcester line and the North Station area, but would also provide a better connection to potential development in Allston. Another branch could circle around the back of the Boston Engine Terminal and serve the third and fourth iron tracks (to the west of the Orange Line) at a major new transfer station at Sullivan before extending to Assembly or perhaps even towards Lynn along the Eastern Route. With these tracks, and the overbuilt (in anticipate on lengthening) Orange Line station, there's plenty of room for such a facility, being a major transfer point and serving a high-potential TOD node. (See page 97 of this urban ring

PDF for engineering drawings.) On the west end, service could be extended west along the Turnpike to the new "Boston Landing" New Balance station, and perhaps further as local service to upgraded Newton stations and a 128 park-and-ride, while current commuter rail service could provide an express trip, local trains serve the inner stations, with cross-platform transfers in Allston.

Kendall has a huge

head start over pretty much anywhere else in the world for biotech (and some other tech as well) and a lot of that is because it has good transportation access, as a commenter in this Universal Hub

thread said a lot of the reason it's grown is that "none of the new hires and hot recruits wanted to move to [exurban] New Jersey." It's well-located. But to truly cement that lead, the community needs to embrace more transit capacity, and an east-west line to complement the north-south Red Line is, I think, the ticket. A winding bus rapid transit line? Probably not.

Then there's the Harvard to Longwood section. In the short term, bus lanes on Mass Ave may be able to help the M2 to better provide this connection. And if West Station is built, a shuttle bus from Harvard to Allston will move commuters along that leg. But in the longer run, this is also a corridor which would benefit greatly from a new, underground, high-capacity transit service. If you're going to tunnel under the LMA (and getting high throughput through the LMA is easier said than done on the surface), it should have rails in it, which allow for higher speed and higher capacity service. Buses in tunnels need to be guided, and are still hamstrung by lower speeds and wide loading profiles. If they're not electric or dual-mode, ventilation is more of an issue than with electric rail. And the cost of a tunnel is the digging itself; it's no cheaper to construct a concrete road in a tunnel than steel rails.

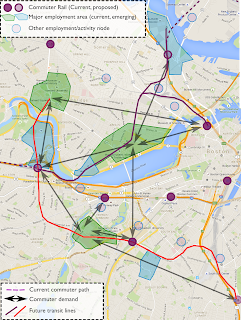

Above: major and emerging employment centers outside of downtown (green, blue), other employment/activity nodes (pink circles), Commuter Rail stations (purple circles). On the left, current transit routes and demand, on the right, how two new rail lines would satisfy most of this demand.

The advantage of buses is that they can run on the surface outside of a tunnel, so you only have to tunnel in the most necessary locations. The disadvantage is that once you build a tunnel for buses, you lose the capacity you might get with rail, so it's a big investment for minimal capacity. The issue with this tunnel is that the most expensive portion to tunnel is also the most necessary: if you build that portion of the tunnel, it makes sense to build logical extensions on either end.

In this case, the line extends in two obvious directions from the ends of this tunnel: towards Harvard Square and towards JFK/UMass station, where it can connect, on both ends, to the Red Line. In both cases, in fact, there are already yard leads in place for this connection. Such a loop would connect all of the South Side rail lines (and the Fitchburg Line at Porter) with Harvard Square, Allston and the LMA. It would provide much better service than any amount of bus rapid transit could for an urban ring. It would cost more to construct, but provide a much better network enhancement by connecting the Commuter Rail lines—all of which have potential to add more capacity—with major employment centers with which they are currently disconnected, and provide far speedier service than any at-grade option.

The easier Red Line connection is on the south end. North of JFK/UMass Station, there Cabot Yard leads extend, grade-separated, north towards South Station and the Red Line yard. This is basically a full two-track subway line for a mile from Columbia to Widett Circle (for what its worth, this line would basically connect all of the Olympic venues Boston2024 has proposed, as well). The next mile and a half to Ruggles could follow the Melnea Cass right of way (cut and cover: cheap, fast and it doesn't impact parking or businesses), which was cleared for the unbuilt Inner Belt highway. Using this right of way would mean that a tunnel could be built below grade as a cut-and-cover project, far cheaper than a bored tunnel, with minimal land takings. It would also serve Boston Medical Center with a subway station.

From there, a tunnel boring machine would be needed under Longwood and Brookline. The launch box for the machine could be built in the Melnea Cass easement on one end and the Allston yards at the other; much of the cost of using such technology comes from the land needed to put the machinery in and out of the ground (see

San Francisco, for example), but in this case, there is open land available. This section would provide an easy connection between the LMA and Ruggles, JFK and West Station, making the area far easier to access from the Commuter Rail system. This tunnel, with stations, would likely cost in the range of $2 to $3 billion. But it would transform the transportation options in the area far more than any other project for decades to come.

From West Station, another cut-and-cover tunnel could be built up towards Harvard Stadium and the under the river (probably a trench-and-box procedure since the river is quite shallow here) towards the JFK School. The state actually

owns the pedestrian corridor through the JFK School campus to the old yard leads which still exist behind a cinderblock wall. (Don't believe me?

Check out these pictures. You could lay track in there tomorrow. More info in this

foamernet thread.) Since Harvard has bi-level platforms, you could run trains on and off of the current trackage there without any crossing traffic since it's a flying junction. Of course, this dramatically limits utility, because you would miss the Harvard station itself which is outbound of the wye.

|

Obviously, just a sketch, but it's likely something

could be fit in to the existing Harvard station without

completely rebuilding it a la 1978-84. |

So you'd have to do some construction in the station. But this might actually be quite easy. The main issue is that to build a full wye, you'd need to have some trains switch levels, which doesn't exactly work. If you didn't have a Central-Allston leg of the wye (which you don't really need, but which you could retain for non-revenue moves), trains could operate through the existing platform and then have a switch just east of the platform end and a curved tunnel to the existing tunnels (with a less-severe curve than the current line). All of this could be built within the existing station cavern. The major change necessary would be to relocate the stairwell from "The Pit" in Harvard Square, but that could use an update after 30 years anyway, and it could potentially be built in between the bi-level tracks (see sketch). Beyond there the tracks would be left-running (think Britain) but the line could fly over itself somewhere (cut and cover in Allston, or perhaps in the bored section) to regain right-side running for the connection to JFK/UMass.

(Update: Note that this is all conceptual, and there are obviously operational and engineering hurdles to overcome. Just like squeezing a four lane busway in to a 35-foot-wide right of way.)

All of this costs a lot of money, but look at the utility that you would gain:

- Coolidge Corner to Harvard: 8 minutes (currently 25-30)

- Ruggles to Allston: 8 minutes (currently 15-25)

- LMA to Harvard: 11 minutes (currently 25-30)

- Ruggles to Harvard: 14 minutes (currently 30-35)

- Dudley to Harvard: 16 minutes (currently 35-40)

- Porter to LMA: 14 minutes (currently 30-35)

You basically kill off the whole hub-and-spoke notion of Boston by putting Harvard Square, Allston and the LMA the same amount of travel time from most subways and commuter lines as downtown. A trip from Natick to Harvard goes from 55 minutes to 30, a trip from Canton to Harvard from 47 to 36, and a trip from Concord to Longwood from 71 to 47. For many commuters, you're saving nearly an hour a day in transit times, and making transit commuting time-competitive with driving, something which, in many cases, it isn't today.

But isn't BRT just as fast? Boston BRT claims a 42% time savings between Dudley and Harvard, going from 57 minutes to 34. This is impressive! Of course, it's not true. The actual scheduled travel time from

Dudley to Harvard ranges from 22 minutes off-peak (on the 1 bus) to 36 minutes at heavy traffic times (via several modes, the Silver Line or Orange Line to Red Line or even the 1). The 66 bus does take this long (including schedule padding coming in to Harvard), but no one would suggest that it is the fastest way to travel between Dudley and Harvard. The loop described above would go from Melnea Cass and Washington Street to Harvard in about 16 minutes, less than half what the current travel time—or promised BRT travel time—affords.

In any case, the four corridors proposed by the Boston BRT study are certainly some of the most important in Boston. And in the short term, they are certainly candidates for better buses. However, trying to install "gold standard" BRT treatments is not necessarily appropriate: in some it would mean kicking cyclists and, yes, vehicles to the curb (literally!) and in others it would mean using the wrong technology for the necessary demand. If Boston had a Bogotá-style network of wide highways—and if it wasn't bisected by a wide river with only a few crossings—then BRT might make more sense for these heavily-traveled corridors. But given the geography of the city, this is not the case.

Do we have the money for this? We should. Obviously, we need to invest in moving the system to a state of good repair. But we also need to keep up with our "competition": many cities are building multi-billion dollar projects to enhance their transit networks. San Francisco is building the

Central Subway and rebuilding the

Transbay Terminal to better connect people and jobs. LA is building several transit

lines and

connections to enhance transit in the city. New York is building the

Second Avenue line, the

7 extension and

East Side Access, among others. Chicago, having

rebuilt many of its elevated lines in recent years, is seriously

talking about the Brown Line flyover. Boston is installing a few

third rail heaters. (The GLX project is a good one, but it is more an extension than it adds capacity to the network.)

We do need to look towards the future. And while other cities are all embracing BRT as part of the solution, they are investing in their rail systems as well. The ITDP's agenda of buses-only is a detriment to that approach, and thus we may run in place while other cities move forward.

In the next post, I'll discuss places where buses could benefit from elements of bus rapid transit, even though it might not fit in to the ITDP's arbitrary standard system.