I'm tired of going to public meetings. Especially meetings organized by businesses in Cambridge where they accuse bicycle advocates of top-down planning which is making the roads unsafe, open the meeting by saying they don't care about data ("then why are we here?") and close by saying the want to collect anecdotes. They go on to complain that there has been no public process (which is interesting, given I've been part of a lot of this process) and say that the facilities are unsafe because they think they look unsafe. Let's look at some of their "arguments" and break them down, and then let's give the public some talking points for pushing back at subsequent meetings.

1. Don't let "them" set the meeting agenda. If a meeting is billed as a "community" meeting, it should be led by the community. If the businesses are taking charge, before the start the meeting, go up to the dais and propose the following: that the meeting be led by a combination of the community members and the business association. Have a volunteer ready to go. If they refuse, propose a vote: let the people in attendance vote on the moderator. If they still refuse, walk out. (This obviously doesn't go for city-led meetings, but for these sham public meetings put on by the business community which are only attended by cyclists if we catch it.)

2. Ask them about business decline data. I don't believe they have it. They claim that business is down because of the bike lanes, but ask by how much, and how many businesses. There is very likely a response bias here. Which businesses are going to complain to the business community about sales being down? The ones with sales which have gone down. Better yet, come armed with data, or at least anecdotes. Go and ask some businesses if their sales have been harmed by the bike lanes. Find ones which have not. Cite those.

3. There has been plenty of public process. The anti-bike people claim that there has been no public process, and that the bike lanes have been a "top-down" process. These arguments are disingenuous, at best. The Cambridge Bicycle Plan was the subject of dozens of meetings and thousands of comments. If residents and businesses didn't know it was occurring, they weren't paying attention. It would also do them some good to come to the monthly Bicycle Advisory Committee meetings, where much of this is discussed (they're open to the public; and committee members take a training on public meeting law to make sure procedures are carried out correctly). These are monthly, advertised meetings. If you don't show up, don't complain about the outcome.

Then there's participatory budgeting. The bike lanes on Cambridge and Brattle streets rose directly from participatory budgeting. This was proposed by a citizen, promoted by citizens, vetted by a citizen committee and voted on by citizens. Yet because the Harvard Square Business Association didn't get a voice (or a veto), it was "top down." They'd propose a process where they dictate the process, which is somehow "grassroots." This is untrue. Don't let them get away with this nonsense. The bike lanes are there because of grassroots community activism. If they don't like them, they had their chance to vote. They lost.

4. Bike lanes cause accidents. After the meeting, a concerned citizen (a.k.a. Skendarian plant) took me aside to tell me a story about how the bike lanes caused an accident. I didn't know what to expect, but they told me that the heard from Skendarian that a person parked their car and opened their door and a passing car hit the door. I was dumbfounded. I asked how the bike lane caused the accident and was told the bike lane made the road too narrow. He liked the old bike lanes, so he could open his door in to the bike lane. So if you hear this story, remember, this was caused by a car hitting a car. And if someone says that bike lanes require them to jaywalk to reach the sidewalk, remind them that 720 CMR 9.09(4)(e) says that a person exiting a car should move to the nearest curb, so crossing the bike lane would be allowable.

5. Data. The anti-bike forces will claim they don't want to use data. There's a reason: the data do not work in their favor. They may claim that the data don't exist. This is wrong. The Cambridge Police Department has more than six years of crash data available for download, coded by location and causation; the Bicycle Master Plan has analyzed his to find the most dangerous locations. Who causes crashes? More than 99 times out of 100: cars. (Note: object 1 is generally the object assumed to be at fault.)

When I dowloaded these data last year, there were 9178 crashes in the database. If someone mentions how dangerous bicyclists hitting pedestrians is, note that in six years, there have been five instances where a cyclist caused a crash with a pedestrian. (This shows up as 0.1% here, it's rounded up from 0.05%. Should this number be less? Certainly. But let's focus on the problem.). There have been 100 times as many vehicles driving in to fixed objects as there have been cyclists hitting pedestrians. Maybe we should ban sign posts and telephone poles.

--

I've written before about rhetoric, and it's important to think before you speak at these sorts of meetings (and, no, I'm not great about this). Stay calm. State your points. No ad hominem (unless someone is really asking for it, i.e. if you're going after the person who says they don't care about bicycle deaths, yeah, mention that). Also, don't clap. Don't boo. Be quiet and respectful, and respect that other people may have opinions, however wrong they may be. When it comes your turn, state who you are and where you live, but not how long you have or haven't lived there. When they go low, go high. We're winning. We can afford to.

Wednesday, November 15, 2017

Saturday, November 4, 2017

Cambridge Council Endorsements

I know you've all been waiting for it … the Official Amateur Planner 2017 Cambridge City Council endorsements!

I've lived in Cambridge for 6 years now, served on the Bicycle Committee for most of that time and gone to more council and zoning meetings than I care to admit. I'm making these endorsements based on two criteria: bicycle safety and progressive development policy (with a bit of transit thrown in). A bit of background:

1. Bicycle safety has become a hot button issue in Cambridge in recent years as more and more people have embraced cycling to work, and our infrastructure hasn't kept up. There is some talk that the recent activism, especially among younger voters, will change the makeup of the electorate in Cambridge this year. Nominally, all candidates are for safe cycling, but in reality, some are more than happy to sell out to the interest of the minority of people driving in Cambridge. After several "pop-up" lanes were installed this spring, there was a bit of "bikelash" in Cambridge, with some City Councilors calling for a moratorium until we could figure out how to make bike lanes not impact—well, something. They're not sure. Let's call it "easy parking and the free flow of traffic." Most insidious: the Harvard Square Business Association trying to kill bike lanes because cars. Councilors Simmons, Toomey and Maher supported this. they're off the list. (They also got their comeuppance: hundreds of cyclists, three hours of public comment and a meeting that ran until after midnight; I doubt they'll be pulling this sort of stunt any time soon.) Craig Kelley, based on several interactions, is kind of wishy-washy on safe cycling infrastructure, and while he often touts himself as a cyclist, he often veers in to the vehicular cycling realm. Sorry, Craig. For others, and for new candidates, I'll defer to the Cambridge Bicycle Safety group's list.

2. Development. Here, most candidates fall in to two camps, the Cambridge Residents Alliance and A Better Cambridge. Both are nominally aligned with allowing more development, but only one—A Better Cambridge—actually follows through. There are a few arguments against additional density and development, none of which hold water:

I've lived in Cambridge for 6 years now, served on the Bicycle Committee for most of that time and gone to more council and zoning meetings than I care to admit. I'm making these endorsements based on two criteria: bicycle safety and progressive development policy (with a bit of transit thrown in). A bit of background:

1. Bicycle safety has become a hot button issue in Cambridge in recent years as more and more people have embraced cycling to work, and our infrastructure hasn't kept up. There is some talk that the recent activism, especially among younger voters, will change the makeup of the electorate in Cambridge this year. Nominally, all candidates are for safe cycling, but in reality, some are more than happy to sell out to the interest of the minority of people driving in Cambridge. After several "pop-up" lanes were installed this spring, there was a bit of "bikelash" in Cambridge, with some City Councilors calling for a moratorium until we could figure out how to make bike lanes not impact—well, something. They're not sure. Let's call it "easy parking and the free flow of traffic." Most insidious: the Harvard Square Business Association trying to kill bike lanes because cars. Councilors Simmons, Toomey and Maher supported this. they're off the list. (They also got their comeuppance: hundreds of cyclists, three hours of public comment and a meeting that ran until after midnight; I doubt they'll be pulling this sort of stunt any time soon.) Craig Kelley, based on several interactions, is kind of wishy-washy on safe cycling infrastructure, and while he often touts himself as a cyclist, he often veers in to the vehicular cycling realm. Sorry, Craig. For others, and for new candidates, I'll defer to the Cambridge Bicycle Safety group's list.

2. Development. Here, most candidates fall in to two camps, the Cambridge Residents Alliance and A Better Cambridge. Both are nominally aligned with allowing more development, but only one—A Better Cambridge—actually follows through. There are a few arguments against additional density and development, none of which hold water:

- Gentrification. In Cambridge, this has already happened. So new luxury housing is not going to "improve" neighborhoods and increase existing rents, despite what CRA may say. This is, in general, grade-A horse manure.

- Road/transit congestion. This too is a red herring. Cambridge itself is not that congested, most people bike, walk and take transit to work. It's the getting to Cambridge part. More local housing will mean more bike/walk/transit commutes, and the answer is not to build less housing, but to improve connections to Cambridge. Yet the CRA won't take a position on reducing parking minimums.

- Open space. There is an argument for keeping some Open Space. But for an organization like CRA, open space becomes "parking lots." This needs no further explanation. (Apparently they have softened it to "it can be redeveloped for affordable housing"—good idea—"but only if the parking is replaced." Just, no.

There have been recent pushes by small groups of residents to downzone parts of Cambridge (I'm not sure if the CRA took a position on this, but they claim that Cambridge faces "over-development"; however, I know ABC opposed it wholeheartedly.) I don't like going to these meetings and don't want to have to go to more! Let's get councilors who we know won't buy in to this nonsense.

A local zoning case in point: There used to be an autobody shop and a couple of businesses in a decaying, single-story building at 78 Pearl Street. These were non-conforming uses, built before the area was zoned C. The land was bought and the businesses relocated. It would have been a perfect opportunity to build a mixed-use, multifamily dwelling with apartments sized appropriately for the area. However, because of the zoning, mixed-use was out (even though it was replacing businesses!) and in place of the building went 78 and 80 Pearl: 4 bedroom, 3.5 bathroom (as a friend said: "oh, so everyone can poop in their own toilet!") single-family houses (on tiny lots) for $1.75 to $2 million. Two units instead of six. There are plenty of examples of non-conforming uses which could never be built today but fit in fine with the neighborhood. But given the land values, and the zoning, developers are forced to build this type of low-density, pseudo-suburban housing which is completely unaffordable.

So, while some CRA-endorsed candidates are beyond excellent on bicycle infrastructure (Jan Devereaux in particular, but she's past president of the very NIMBY Fresh Pond Residents Alliance, so there's that), this page can not endorse anyone who is endorsed by the CRA. If you're voting just based on bikes, she should be on your list.

There is some "whataboutism" going on with some anti-development types who say that the fault lies in other cities and towns not doing their part. This is true, but it's no reason for Cambridge not to develop more housing as well. Remember when Homer Simpson ran a campaign for garbage commissioner with the slogan "can't someone else do it?" Can't someone else do it is not a logical policy. Yes, there would be less pressure on local housing prices if the Newtons of the world did their part. But it's no reason for Cambridge to keep density down.

So, while some CRA-endorsed candidates are beyond excellent on bicycle infrastructure (Jan Devereaux in particular, but she's past president of the very NIMBY Fresh Pond Residents Alliance, so there's that), this page can not endorse anyone who is endorsed by the CRA. If you're voting just based on bikes, she should be on your list.

There is some "whataboutism" going on with some anti-development types who say that the fault lies in other cities and towns not doing their part. This is true, but it's no reason for Cambridge not to develop more housing as well. Remember when Homer Simpson ran a campaign for garbage commissioner with the slogan "can't someone else do it?" Can't someone else do it is not a logical policy. Yes, there would be less pressure on local housing prices if the Newtons of the world did their part. But it's no reason for Cambridge to keep density down.

Oh, then there's Tim Toomey. He's already out for a number of reasons (when he was a Councilor and State Rep, he was making more money than the governor, so don't feel bad if he loses his job, his pension should be just fine), but please leave him off your ballot entirely. He quashed the idea of running commuter rail to Cambridge because he was afraid of big, bad trains running on train tracks, so instead everyone from the Metrowest/Turnpike corridor drives. More congestion! More pollution! Progress! Thanks, Tim.

So with these criteria in mind, here are the official Amateur Planner-endorsed candidates. It's easy to remember: they all begin with "M":

- Alanna Mallon: I met Alanna when she was canvassing. She gets it. I think she didn't get the Bike Safety endorsement because she holds back a bit on implementation of bike lanes. But from my conversation, she is very much in favor of transit and bike lanes, and will be an ally on the Council.

- Marc McGovern: Marc has been on the Council since I've lived in Cambridge, and has been on the right side of the debate the whole time. I look forward to him serving another term.

- Adriane Musgrave: I may have talked to Adriane longer than I talked to Alanna! (Note to candidates: knocking on my door helps.) She also very much "gets it" and is super data-driven and wonky. That's my kind of candidate!

So there you have it. If these three candidates are on the City Council, the future is bright. I will be ranking them #1, 2 and 3. (I'm not giving away my order.) If you live in Cambridge, vote how you wish. But I would urge you to vote for these candidates.

(I don't live in Boston, but here's my at-large council endorsement for Michelle Wu, of course. )

(I don't live in Boston, but here's my at-large council endorsement for Michelle Wu, of course. )

Friday, October 27, 2017

Thinking Big? Let's Think "Realistic" First

The MBTA's Fiscal and Management Control Board, according to their slides, wants to “think big.”

Thinking big is a laudable goal. The only problem is that big thinking requires feasibility, and it is a waste of everyone’s time and energy if the big thinking is completely outside the realm of what can reasonably occur or be built.

Thinking big is a laudable goal. The only problem is that big thinking requires feasibility, and it is a waste of everyone’s time and energy if the big thinking is completely outside the realm of what can reasonably occur or be built.

Case in point: combining Park Street and Downtown Crossing into one “superstation.” The first reason this won’t happen is that it doesn’t need to happen: with the concourse above the Red Line between the two stations, they are already one complex. (#Protip: it’s faster to transfer between the Red Line at Park and the Winter Street platform on the Orange Line—trains towards Forest Hills for the less anachronistic among us—by walking swiftly down the concourse rather than getting on the train at Downtown Crossing.) But there are several other reasons why this is just not possible.

Tangent track

To build a new station between Park Street and Downtown Crossing would require tangent, or straight, track. If you stand at Park, however, you can’t see Downtown Crossing, because the tracks, which are separated for the center platform at Park, curve back together for the side platforms at Downtown Crossing. This curve is likely too severe to provide level boarding, so the track would have to be realigned through this segment. So even if it were easy to build a new complex here, the tracks would have to somehow be rebuilt without disrupting normal service. That’s not easy.

Winter Street is narrow. Really narrow.

The next, and related, point: Winter Street is very narrow: only about 35 feet between buildings. Park Street Station is located under the Common, and the Red Line station at Downtown Crossing is located under a much wider portion of Summer Street: those locations have room for platforms. Winter Street does not. Two Red Line tracks require about 24 feet of real estate: this would leave 5.5 feet for platforms on either side before accounting for any vertical circulation, utilities and the like. Any more than that and you’re digging underneath the century-old buildings which give the area its character. That’s not about to happen. And Winter Street would be the only logical location for the station; otherwise it would force long walks for transferring passengers.

Note the photograph to the right. The current Downtown Crossing station is located between Jordan Marsh on the left and Filene's on the right (for newer arrivals: the Macy's and the Millenium building), where Summer Street is about 60 feet wide, enough for two tracks and platforms, and it's still constrained, with entrances in the Filene's and Jordan Marsh buildings. Note in the background how much narrower Winter Street is. This isn't an optical illusion: it's only half as wide. The only feasible location for such a superstation would be between the Orange and Green lines, but the street there is far too narrow.

Passenger operations

The idea behind combining Downtown Crossing and Park Street is that it would simplify signaling and allow better throughput on the line operationally. But any savings from operations would likely be eaten by increased dwell times at these stations. At most stations, the T operations are abysmal regarding dwell times; Chicago L trains, for example, rarely spend as much time in stations as MBTA trains do, as the operator will engage the door close button as soon as the doors open. At Park and Downtown Crossing, however, this is not the case. Long dwell times there occur because of the crowding: at each station, hundreds of passengers have to exit the train, often onto a platform with as many waiting to board. This is rather unique to the T, and the Red Line in particular, which, between South Station and Kendall, is at capacity in both directions. Trying to unload and then load nearly an entire train worth of passengers at one station, even with more wider doors on new cars, just doesn’t make sense.

If Park and Downtown Crossing were little-used stations, it would make no sense to have two platforms 500 feet apart, and combining them, or just closing one, would be sensible. (Unlike New York and Chicago, the Boston Elevated Railway never built stations so close that consolidation was necessary.) But they are two of the busiest stations in the MBTA system, both for boardings and for transfers. Given the geometry of the area, both above and below ground, calling this a big idea is risible. Big ideas have to, at least, be somewhere in the realm of reality. Without a 1960s-style wholesale demolition of half of Downtown Boston, this is a distraction. The FMCB has a lot to do: they should not spend time chasing unicorns.

Better Headways? Geometry gets in the way, not just signals.

In addition to a spending time on infeasible ideas like combining Park and Downtown Crossing, the FMCB and T operations claims that it would only take a minor signal upgrade (well, okay, any signal upgrade wouldn't be minor) to allow three minute headways on the Red Line. Right now, trains come every 4 to 4.5 minutes at rush hour (8 to 9 minutes each from Braintree and Ashmont); so this would be a 50% increase. Three minute headways are certainly a good idea, but the Red Line especially has several bottlenecks which would have to be significantly upgraded before headways can progress much below their current levels. New signals would certainly help operations, but they are not the current rate limiting factor for throughput on the line.

There are four site-specific major bottlenecks on the line beyond signaling: the interlocking north of JFK-UMass (a.k.a. Malfunction Junction), the Park-Downtown Crossing complex, the Harvard curve, and the Alewife terminal. (In addition, the line’s profile, which has a bi-directional peak along its busiest portion, results in long dwell times at many stations.) Each of these is it’s own flavor of bottleneck, and it may be informative to look at them as examples of how retrofitting a century-old railroad is easier said than done. This is not to say that a new signaling system shouldn’t be installed: it absolutely should! It just won’t allow for three minute headways without several other projects as well. From south to north:

JFK-UMass

This is likely the easiest of the bottlenecks to fix: it’s simply an interlocking which needs to be replaced. While the moniker Malfunction Junction may not be entirely deserved (the Red Line manages to break down for many other reasons), it is an inefficient network of special track work which dates to the early 1970s and could certainly use an upgrade. In fact, it probably would be replaced, or significantly improved, with the installation of a new signal system.

Park/Downtown

Right now, Park and Downtown Crossing cause delays because of both signaling and passenger loads. For instance, a train exchanging passengers at Downtown Crossing causes restricted signals back to Charles, so that it is not possible for trains to load and unload passengers simultaneously at Park and Downtown Crossing. Given the passenger loads at these stations and long dwell times at busy times of day, it takes three or four minutes for a train to traverse the segment between the tunnel portal at Charles and the departure from Downtown Crossing, which is the current rate-limiting factor for the line. If you ever watch trains on the Longfellow from above (and my new office allows for that, so, yeah, I’m real productive at work), you can watch the signal system in action: trains are frequently bogged down on the bridge by signals at Park.

A new signal system with shorter blocks or, more likely, moving blocks would solve some of this problem. A good moving block system would have to allow three trains to simultaneously stop at Park, Downtown Crossing and South Station. So this would be solved, right? Well, not exactly. Dwell times are still long at all three of these stations: as they are among the most heavily-used in the system. Delivering reliable three-minute headways would help with capacity, but longer headways would lead to cascading delays if trains were overcrowded. There’s not much margin for error when trains are this close together. Given the narrow, crowded stairs and platforms at Park and Downtown crossing, the limiting factor here is probably passenger flow: it might be hard to clear everyone from the platforms in the time between dwells. And it is not cheap to try to widen platforms and egress. A new signaling system would help, but this still may be a factor in delivering three minute headways.

The Harvard Curve and dwell times

Moving north, the situation doesn’t get any easier to remedy. When the Red Line was extended past Harvard, the President and Fellows of Harvard College would not allow the T to tunnel under the Yard, so the T was forced to stay in the alignment of Mass Ave. This required the curve just south of the station, which is limited (and will always be limited) to 10 miles per hour. The curve itself is about 400 feet long, but if any portion of the train (also about 400 feet long) is in the curve, it is required to remain at this restricted speed. So the train has to operate for 800 feet at 10 mph, which takes about 55 seconds to operate this segment alone. Given that with Harvard’s crowds, it has longer dwell times due to passenger flow, traversing the 800 feet of track within the station and tunnel beyond takes more than two minutes under the best of circumstances.

Would signaling help? Maybe somewhat, but not much. Even a moving block signal system would not likely allow a train to occupy the Harvard Platform with another train still in the curve. Chicago has 25 mph curves on the Blue Line approaching Clark/Lake and operates three minute headways, but they also frequently bypass signals to pull trains within feet of each other to stage them, something the T would likely be reticent to do. It may be possible to operate these headways but with basically zero margin for error. Any delay, even small issues beyond the control of the agency, would quickly cascade, eating up any gains made from running trains more frequently. This is a question of geometry more than anything else: if trains could arrive and leave Harvard at speed, it wouldn’t be an issue. But combining the dwell time and the curve, nearly the entire headway is used up just getting through the station.

Alewife

The three issues above? They pale in comparison to Alewife. Why? Because Alewife was never designed to be a terminal station. (Thanks, Arlington.) The original plan was to extend the Red Line to 128, with a later plan to bring it to Arlington Heights. But these plans were opposed by the good people of Arlington, and the terminal wound up at Alewife. The issues is that the crossover, which allows trains to switch tracks at the end of the line, didn’t. It wound up north of Russell Field, along a short portion of tangent track between the Fitchburg Cutoff right-of-way and the Alewife station, and about 900 feet from the end of the platform. If a train uses the northbound platform, it can run in to the station at track speed (25 mph, taking 50 seconds), unload and load at the platform, and allow operators to change ends (with drop back crews, this can take 60 seconds), and then pull out 900 feet (25 mph, taking 30 seconds) and run through the crossover at 10 mph (45 seconds). That cycle takes 185 seconds, or just about three minutes, of which about a minute is spent traversing the extra distance in and out of the station. If the train is crossing over from one track to the other would foul the interlocking, causing approaching trains to back up. And since this is at the end of the line, there’s significant variability to headways coming in to the station, so trains are frequently delayed between Alewife and Davis waiting for tracks to clear.

Without going in to too much detail, the MBTA currently has a minimum target of about 4 minute headways coming out of Alewife. Without rebuilding the interlocking—and there’s nowhere to do this, because it’s the only tangent portion of track, and interlockings basically have to be built on tangent track—there’s no way to get to three minute headways. In addition, the T is in the enviable position of having strong bidirectional ridership on the Red Line. In many cities, ridership is unbalanced: Chicago, for example, runs three minute headways on their Red Line from Howard at peak, but six minutes in the opposite direction from 95th (this results in a lot of "deadheading" where operators are paid to ride back on trains to get back to where they came from). The T needs as many trains as it can run in both directions, so it has to turn everything at Alewife (never mind the fact that there’s no yard beyond; we'll get to that). This also means that T has to run better-than-5-minute headways until 10 a.m. and 8 p.m. to accommodate both directions of ridership. While this means short wait times for customers, it incurs extra operational costs, since these trains provide more service than capacity likely requires and, for instance, we don't need a train leaving Alewife every four minutes at 9:30, except we have to put the trains somewhere back south.

In the long run, to add service, Alewife is probably unworkable. But there is a solution, I think. The tail tracks extend out under Route 2 and to Thorndike Field in Arlington. The field itself is almost exactly the size of Codman Yard in Dorchester. Assuming there aren’t any major utilities, the field could be dug up, an underground yard could be built with a new three-track, two-platform station adjacent to the field (providing better access for the many pedestrians who walk from Arlington, with Alewife still serving as the bus transfer and park-and-ride), a run-through loop track, and a storage yard. I have a very rough sketch of this in Google Maps here.

Assuming you could appease local population and 4(f) park regulations, the main issue is that field itself is quite low in elevation—any facility would be below sea level and certainly below the water table. But if this could be mitigated, it would be perhaps the only feasible way to add a yard to the north end of the Red Line. And it is possible that a yard in Arlington, coupled with some expansion of Codman (which has room for several more tracks) could eliminate the need for the yard facility at Cabot Yard in Boston, which is a long deadhead move from JFK/UMass station. While the shops would still be needed the yard, which sits on six acres of real estate a ten minute walk on Dot Ave from Broadway and South Station, could fetch a premium on the current real estate market.

This wouldn’t be free, and would take some convincing for those same folks in Arlington, but operationally, it would certainly make the Red Line easier to run. Upgrades to signals and equipment will help, but if you don’t fix Alewife, you have no chance of running more trains.

Overall, I'm not trying to be negative here, I'm just trying to ground ideas in realism. It's fun to think of ways to improve the transit system, but far too often it seems that both advocates and agencies go too far down the road looking in to ideas which have no chance of actually happening. We have an old system with good bones, but those bones are sometimes crooked. When we come up with new ideas for transit and mobility, we need to take a step back and make sure they'll work before we go too much further.

Today's glossary:

Editor's note: after a busy first half of the semester, I have some more time on my hands and should be posting more than once every two months!

Thinking big is a laudable goal. The only problem is that big thinking requires feasibility, and it is a waste of everyone’s time and energy if the big thinking is completely outside the realm of what can reasonably occur or be built.

Thinking big is a laudable goal. The only problem is that big thinking requires feasibility, and it is a waste of everyone’s time and energy if the big thinking is completely outside the realm of what can reasonably occur or be built.Case in point: combining Park Street and Downtown Crossing into one “superstation.” The first reason this won’t happen is that it doesn’t need to happen: with the concourse above the Red Line between the two stations, they are already one complex. (#Protip: it’s faster to transfer between the Red Line at Park and the Winter Street platform on the Orange Line—trains towards Forest Hills for the less anachronistic among us—by walking swiftly down the concourse rather than getting on the train at Downtown Crossing.) But there are several other reasons why this is just not possible.

Tangent track

To build a new station between Park Street and Downtown Crossing would require tangent, or straight, track. If you stand at Park, however, you can’t see Downtown Crossing, because the tracks, which are separated for the center platform at Park, curve back together for the side platforms at Downtown Crossing. This curve is likely too severe to provide level boarding, so the track would have to be realigned through this segment. So even if it were easy to build a new complex here, the tracks would have to somehow be rebuilt without disrupting normal service. That’s not easy.

Winter Street is narrow. Really narrow.

The next, and related, point: Winter Street is very narrow: only about 35 feet between buildings. Park Street Station is located under the Common, and the Red Line station at Downtown Crossing is located under a much wider portion of Summer Street: those locations have room for platforms. Winter Street does not. Two Red Line tracks require about 24 feet of real estate: this would leave 5.5 feet for platforms on either side before accounting for any vertical circulation, utilities and the like. Any more than that and you’re digging underneath the century-old buildings which give the area its character. That’s not about to happen. And Winter Street would be the only logical location for the station; otherwise it would force long walks for transferring passengers.

|

| Summer Street (foreground) is wide. Winter Street (background) is narrow. The fact that so many streets change names crossing Washington? Well, that's just confusing. |

Note the photograph to the right. The current Downtown Crossing station is located between Jordan Marsh on the left and Filene's on the right (for newer arrivals: the Macy's and the Millenium building), where Summer Street is about 60 feet wide, enough for two tracks and platforms, and it's still constrained, with entrances in the Filene's and Jordan Marsh buildings. Note in the background how much narrower Winter Street is. This isn't an optical illusion: it's only half as wide. The only feasible location for such a superstation would be between the Orange and Green lines, but the street there is far too narrow.

Passenger operations

The idea behind combining Downtown Crossing and Park Street is that it would simplify signaling and allow better throughput on the line operationally. But any savings from operations would likely be eaten by increased dwell times at these stations. At most stations, the T operations are abysmal regarding dwell times; Chicago L trains, for example, rarely spend as much time in stations as MBTA trains do, as the operator will engage the door close button as soon as the doors open. At Park and Downtown Crossing, however, this is not the case. Long dwell times there occur because of the crowding: at each station, hundreds of passengers have to exit the train, often onto a platform with as many waiting to board. This is rather unique to the T, and the Red Line in particular, which, between South Station and Kendall, is at capacity in both directions. Trying to unload and then load nearly an entire train worth of passengers at one station, even with more wider doors on new cars, just doesn’t make sense.

If Park and Downtown Crossing were little-used stations, it would make no sense to have two platforms 500 feet apart, and combining them, or just closing one, would be sensible. (Unlike New York and Chicago, the Boston Elevated Railway never built stations so close that consolidation was necessary.) But they are two of the busiest stations in the MBTA system, both for boardings and for transfers. Given the geometry of the area, both above and below ground, calling this a big idea is risible. Big ideas have to, at least, be somewhere in the realm of reality. Without a 1960s-style wholesale demolition of half of Downtown Boston, this is a distraction. The FMCB has a lot to do: they should not spend time chasing unicorns.

Better Headways? Geometry gets in the way, not just signals.

In addition to a spending time on infeasible ideas like combining Park and Downtown Crossing, the FMCB and T operations claims that it would only take a minor signal upgrade (well, okay, any signal upgrade wouldn't be minor) to allow three minute headways on the Red Line. Right now, trains come every 4 to 4.5 minutes at rush hour (8 to 9 minutes each from Braintree and Ashmont); so this would be a 50% increase. Three minute headways are certainly a good idea, but the Red Line especially has several bottlenecks which would have to be significantly upgraded before headways can progress much below their current levels. New signals would certainly help operations, but they are not the current rate limiting factor for throughput on the line.

There are four site-specific major bottlenecks on the line beyond signaling: the interlocking north of JFK-UMass (a.k.a. Malfunction Junction), the Park-Downtown Crossing complex, the Harvard curve, and the Alewife terminal. (In addition, the line’s profile, which has a bi-directional peak along its busiest portion, results in long dwell times at many stations.) Each of these is it’s own flavor of bottleneck, and it may be informative to look at them as examples of how retrofitting a century-old railroad is easier said than done. This is not to say that a new signaling system shouldn’t be installed: it absolutely should! It just won’t allow for three minute headways without several other projects as well. From south to north:

JFK-UMass

This is likely the easiest of the bottlenecks to fix: it’s simply an interlocking which needs to be replaced. While the moniker Malfunction Junction may not be entirely deserved (the Red Line manages to break down for many other reasons), it is an inefficient network of special track work which dates to the early 1970s and could certainly use an upgrade. In fact, it probably would be replaced, or significantly improved, with the installation of a new signal system.

Park/Downtown

Right now, Park and Downtown Crossing cause delays because of both signaling and passenger loads. For instance, a train exchanging passengers at Downtown Crossing causes restricted signals back to Charles, so that it is not possible for trains to load and unload passengers simultaneously at Park and Downtown Crossing. Given the passenger loads at these stations and long dwell times at busy times of day, it takes three or four minutes for a train to traverse the segment between the tunnel portal at Charles and the departure from Downtown Crossing, which is the current rate-limiting factor for the line. If you ever watch trains on the Longfellow from above (and my new office allows for that, so, yeah, I’m real productive at work), you can watch the signal system in action: trains are frequently bogged down on the bridge by signals at Park.

A new signal system with shorter blocks or, more likely, moving blocks would solve some of this problem. A good moving block system would have to allow three trains to simultaneously stop at Park, Downtown Crossing and South Station. So this would be solved, right? Well, not exactly. Dwell times are still long at all three of these stations: as they are among the most heavily-used in the system. Delivering reliable three-minute headways would help with capacity, but longer headways would lead to cascading delays if trains were overcrowded. There’s not much margin for error when trains are this close together. Given the narrow, crowded stairs and platforms at Park and Downtown crossing, the limiting factor here is probably passenger flow: it might be hard to clear everyone from the platforms in the time between dwells. And it is not cheap to try to widen platforms and egress. A new signaling system would help, but this still may be a factor in delivering three minute headways.

The Harvard Curve and dwell times

Moving north, the situation doesn’t get any easier to remedy. When the Red Line was extended past Harvard, the President and Fellows of Harvard College would not allow the T to tunnel under the Yard, so the T was forced to stay in the alignment of Mass Ave. This required the curve just south of the station, which is limited (and will always be limited) to 10 miles per hour. The curve itself is about 400 feet long, but if any portion of the train (also about 400 feet long) is in the curve, it is required to remain at this restricted speed. So the train has to operate for 800 feet at 10 mph, which takes about 55 seconds to operate this segment alone. Given that with Harvard’s crowds, it has longer dwell times due to passenger flow, traversing the 800 feet of track within the station and tunnel beyond takes more than two minutes under the best of circumstances.

Would signaling help? Maybe somewhat, but not much. Even a moving block signal system would not likely allow a train to occupy the Harvard Platform with another train still in the curve. Chicago has 25 mph curves on the Blue Line approaching Clark/Lake and operates three minute headways, but they also frequently bypass signals to pull trains within feet of each other to stage them, something the T would likely be reticent to do. It may be possible to operate these headways but with basically zero margin for error. Any delay, even small issues beyond the control of the agency, would quickly cascade, eating up any gains made from running trains more frequently. This is a question of geometry more than anything else: if trains could arrive and leave Harvard at speed, it wouldn’t be an issue. But combining the dwell time and the curve, nearly the entire headway is used up just getting through the station.

Alewife

The three issues above? They pale in comparison to Alewife. Why? Because Alewife was never designed to be a terminal station. (Thanks, Arlington.) The original plan was to extend the Red Line to 128, with a later plan to bring it to Arlington Heights. But these plans were opposed by the good people of Arlington, and the terminal wound up at Alewife. The issues is that the crossover, which allows trains to switch tracks at the end of the line, didn’t. It wound up north of Russell Field, along a short portion of tangent track between the Fitchburg Cutoff right-of-way and the Alewife station, and about 900 feet from the end of the platform. If a train uses the northbound platform, it can run in to the station at track speed (25 mph, taking 50 seconds), unload and load at the platform, and allow operators to change ends (with drop back crews, this can take 60 seconds), and then pull out 900 feet (25 mph, taking 30 seconds) and run through the crossover at 10 mph (45 seconds). That cycle takes 185 seconds, or just about three minutes, of which about a minute is spent traversing the extra distance in and out of the station. If the train is crossing over from one track to the other would foul the interlocking, causing approaching trains to back up. And since this is at the end of the line, there’s significant variability to headways coming in to the station, so trains are frequently delayed between Alewife and Davis waiting for tracks to clear.

Without going in to too much detail, the MBTA currently has a minimum target of about 4 minute headways coming out of Alewife. Without rebuilding the interlocking—and there’s nowhere to do this, because it’s the only tangent portion of track, and interlockings basically have to be built on tangent track—there’s no way to get to three minute headways. In addition, the T is in the enviable position of having strong bidirectional ridership on the Red Line. In many cities, ridership is unbalanced: Chicago, for example, runs three minute headways on their Red Line from Howard at peak, but six minutes in the opposite direction from 95th (this results in a lot of "deadheading" where operators are paid to ride back on trains to get back to where they came from). The T needs as many trains as it can run in both directions, so it has to turn everything at Alewife (never mind the fact that there’s no yard beyond; we'll get to that). This also means that T has to run better-than-5-minute headways until 10 a.m. and 8 p.m. to accommodate both directions of ridership. While this means short wait times for customers, it incurs extra operational costs, since these trains provide more service than capacity likely requires and, for instance, we don't need a train leaving Alewife every four minutes at 9:30, except we have to put the trains somewhere back south.

In the long run, to add service, Alewife is probably unworkable. But there is a solution, I think. The tail tracks extend out under Route 2 and to Thorndike Field in Arlington. The field itself is almost exactly the size of Codman Yard in Dorchester. Assuming there aren’t any major utilities, the field could be dug up, an underground yard could be built with a new three-track, two-platform station adjacent to the field (providing better access for the many pedestrians who walk from Arlington, with Alewife still serving as the bus transfer and park-and-ride), a run-through loop track, and a storage yard. I have a very rough sketch of this in Google Maps here.

Assuming you could appease local population and 4(f) park regulations, the main issue is that field itself is quite low in elevation—any facility would be below sea level and certainly below the water table. But if this could be mitigated, it would be perhaps the only feasible way to add a yard to the north end of the Red Line. And it is possible that a yard in Arlington, coupled with some expansion of Codman (which has room for several more tracks) could eliminate the need for the yard facility at Cabot Yard in Boston, which is a long deadhead move from JFK/UMass station. While the shops would still be needed the yard, which sits on six acres of real estate a ten minute walk on Dot Ave from Broadway and South Station, could fetch a premium on the current real estate market.

This wouldn’t be free, and would take some convincing for those same folks in Arlington, but operationally, it would certainly make the Red Line easier to run. Upgrades to signals and equipment will help, but if you don’t fix Alewife, you have no chance of running more trains.

Overall, I'm not trying to be negative here, I'm just trying to ground ideas in realism. It's fun to think of ways to improve the transit system, but far too often it seems that both advocates and agencies go too far down the road looking in to ideas which have no chance of actually happening. We have an old system with good bones, but those bones are sometimes crooked. When we come up with new ideas for transit and mobility, we need to take a step back and make sure they'll work before we go too much further.

Today's glossary:

- Deadhead: running out of service without passengers. All the cost of running a train (or, if an operator is riding an in-service train, all the costs of paying them), none of the benefits.

- Headway: the time between train arrivals

- Tangent track: straight track

Editor's note: after a busy first half of the semester, I have some more time on my hands and should be posting more than once every two months!

Monday, August 21, 2017

North Station doesn't belong on the North-South Rail Link

The North South Rail Link has been bubbling up in the news recently (only partially because of me); perhaps as Boston realizes that it won't meet the needs of the next century by expanding on the mistakes of the past. Now comes word that a Harvard-led team examined the cost of the project and found that while it would be costly, it wouldn't be the $15 billion Big-Dig-esque boondoggle the Romney administration feared when it sidelined the project in 2006. (Remember that when the T doesn't want to build something, they just make up numbers.) Given the immense savings from the project and the potential to free up huge parcels of prime real estate (that's the topic of another post entirely), the $4 to $6 billion proposal is right in the ballpark of where a realistic cost-benefit analysis would show long-term benefits, despite the initial cost.

But I'm not going to touch on that (today, at least). I am going to touch on a mistake that everyone makes when they talk about the NSRL: the inclusion of North Station. That's right. I don't think North Station belongs in the North-South Rail Link, because North Station is not now—nor has it ever been—in the right location. Since we're talking about building an entirely new station 80 feet underground, there's no rule which says that we have to have the exact same stations. South Station belongs. North doesn't.

Let's look at the current downtown stations in Boston. Here's South Station and Back Bay, showing everything within a half mile:

South Station is surrounded by some highway ramps and water, but otherwise well-located in between the Financial District and the Seaport, and it also has a Red Line connection. Now, here's North Station:

See the problem here? Note how nearly everything to the north of North Station has no real use: it's highway ramps, river, and parking lots. No housing. No jobs. So that when people get off the train at North Station, they almost invariably walk south, towards South Station. You could move North Station half a mile south and pretty much everyone would still be within half a mile of the train station. North Station has never been in the right location, but is there as an accident of history: it was as close in as they could build a station nearly 200 years ago (well, a series of stations for several railroads) without bulldozing half the city. It's the right place for a surface station, but if you have the chance to build underground, it's not.

Most NSRL plans try to mitigate this with a third, Central station, somewhere near Aquarium Station, but this has the same issue as North Station: half of the catchment area is in the Harbor:

This would give you three stations doing the job of two. Each train would have to stop three times, but the two northern stops could easily be replaced by a single stop somewhere in between. I nominate City Hall plaza. It would connect to the Orange, Green and Blue lines (at Government Center and Haymarket) and, if you draw a circle around it, it wouldn't wind up with half of the circle containing fish.

North Station would still be served by the Orange and Green lines, and it would allow the North-South Rail Link to serve the efficiently and effectively serve the greatest number of passengers. A pair of stations in Sullivan Square and near Lechmere could allow regional access to the areas north of the river, which would sit on prime real estate if the tracks were no longer needed (they'd be underground). Since stations are much more expensive to build than tunnels (you can bore a tunnel more easily than a station), it might wind up cheaper, too.

Putting it all together, here's a map showing the areas accessible under both the two-station and three-station schemes. Shown without any shading are areas within half a mile of the stations in both plans. Red areas are areas which are within a half mile of the three-station plan but not the two station plan, blue areas are within half a mile of stations in the two-station plan but not the three-station.

This shows that if you are willing to put a station in the vicinity of Government Center, you can get the same coverage in downtown Boston with just two stations. You lose the areas shaded in red, but these are mostly water and highway ramps. Instead, you gain most of Beacon Hill and the State House. It seems like a fair trade. (Yes, you lose direct access for Commuter Rail from North Station during major events at the Garden, but a Government Center/Haymarket station would only be a six minute walk away, or a two minute ride on two subway lines.)

In Commonwealth Magazine, I said that we shouldn't double-down on the mistakes of the past by building larger, inefficient stub-end terminals. The same goes for North Station. The station itself is in the wrong place. If we build a North-South Rail Link, there's no need to replicate it just because it's always been there. Downtown Boston is compact enough it only needs two stations (plus the third at Back Bay). North Station isn't one of them.

But I'm not going to touch on that (today, at least). I am going to touch on a mistake that everyone makes when they talk about the NSRL: the inclusion of North Station. That's right. I don't think North Station belongs in the North-South Rail Link, because North Station is not now—nor has it ever been—in the right location. Since we're talking about building an entirely new station 80 feet underground, there's no rule which says that we have to have the exact same stations. South Station belongs. North doesn't.

Let's look at the current downtown stations in Boston. Here's South Station and Back Bay, showing everything within a half mile:

South Station is surrounded by some highway ramps and water, but otherwise well-located in between the Financial District and the Seaport, and it also has a Red Line connection. Now, here's North Station:

See the problem here? Note how nearly everything to the north of North Station has no real use: it's highway ramps, river, and parking lots. No housing. No jobs. So that when people get off the train at North Station, they almost invariably walk south, towards South Station. You could move North Station half a mile south and pretty much everyone would still be within half a mile of the train station. North Station has never been in the right location, but is there as an accident of history: it was as close in as they could build a station nearly 200 years ago (well, a series of stations for several railroads) without bulldozing half the city. It's the right place for a surface station, but if you have the chance to build underground, it's not.

Most NSRL plans try to mitigate this with a third, Central station, somewhere near Aquarium Station, but this has the same issue as North Station: half of the catchment area is in the Harbor:

This would give you three stations doing the job of two. Each train would have to stop three times, but the two northern stops could easily be replaced by a single stop somewhere in between. I nominate City Hall plaza. It would connect to the Orange, Green and Blue lines (at Government Center and Haymarket) and, if you draw a circle around it, it wouldn't wind up with half of the circle containing fish.

North Station would still be served by the Orange and Green lines, and it would allow the North-South Rail Link to serve the efficiently and effectively serve the greatest number of passengers. A pair of stations in Sullivan Square and near Lechmere could allow regional access to the areas north of the river, which would sit on prime real estate if the tracks were no longer needed (they'd be underground). Since stations are much more expensive to build than tunnels (you can bore a tunnel more easily than a station), it might wind up cheaper, too.

Putting it all together, here's a map showing the areas accessible under both the two-station and three-station schemes. Shown without any shading are areas within half a mile of the stations in both plans. Red areas are areas which are within a half mile of the three-station plan but not the two station plan, blue areas are within half a mile of stations in the two-station plan but not the three-station.

This shows that if you are willing to put a station in the vicinity of Government Center, you can get the same coverage in downtown Boston with just two stations. You lose the areas shaded in red, but these are mostly water and highway ramps. Instead, you gain most of Beacon Hill and the State House. It seems like a fair trade. (Yes, you lose direct access for Commuter Rail from North Station during major events at the Garden, but a Government Center/Haymarket station would only be a six minute walk away, or a two minute ride on two subway lines.)

In Commonwealth Magazine, I said that we shouldn't double-down on the mistakes of the past by building larger, inefficient stub-end terminals. The same goes for North Station. The station itself is in the wrong place. If we build a North-South Rail Link, there's no need to replicate it just because it's always been there. Downtown Boston is compact enough it only needs two stations (plus the third at Back Bay). North Station isn't one of them.

Friday, August 11, 2017

Improving the Providence Line as a stepping stone to Regional Rail

Of all the peculiarities in the MBTA's Commuter Rail operation, one of the most apparent is the Providence Line. Where else can you find a modern, high-speed, electrified railroad with diesel-powered trains operating underneath the wire? Basically nowhere. Yet the MBTA incongruously runs diesels on the line, and not only that, it doesn’t spec its equipment for more than 80 mph, so the trains run at half of the top speed. The Providence Line is the system's busiest, with upwards of 1000 passengers boarding daily at each station, but most board via the trains' steps, lengthening dwell times considerably. It's a 21st century railroad, but the MBTA runs it like the 19th. This provides far worse service than it should and costs the T—and the taxpayer—a lot of money while providing far less public benefit, in terms of regional connectivity and short travel times, as it could. Electrification would also allow for much more efficient utilization of equipment: with the same number of crews and cars on the line today, it would allow twice as many trains at rush hour.

Electrifying the Providence Line for the MBTA would not be trivial, but the costs would be relatively low given the existing infrastructure, and it provide benefits not just for Providence Line riders but for Amtrak riders and nearby residents. It would allow the diesel equipment on the Providence Line to move to other parts of the system, replacing the oldest equipment elsewhere. It would also be the first step towards building Regional Rail: a rail system which not only takes workers downtown at rush hour, but also provides mobility across the region. And where better to start than between the capital cities of Massachusetts and Rhode Island?

This post will address several of the benefits of upgrading the Providence Line to accommodate fast, electric rolling stock, and how they will allow the MBTA and RIDOT (which subsidizes the portion of the line serving Rhode Island) to increase service, decrease operating costs, and provide a better, more competitive product on the rails. With the MBTA's fleet aging, it's high time to examine the future needs of the network, and to begin the move to electric operation and a Regional Rail system.

Electric trains are cheaper to buy

The MBTA's most recent locomotive procurement had a unit cost of $6 million. The unit cost for the M8s delivered to MetroNorth has been in the range of $2.25 to $2.5 million, about the same as an MBTA Rotem bilevel coach. While the bilevel coaches do have more capacity than the single-level cars, a locomotive and six bilevels has the same capacity and costs the same amount as a train of eight EMUs. (Bilevel EMUs are also an option, although Northeast Corridor-spec'ed bilevel equipment does not yet exist, New Jersey may order some soon. If so, costs may not be appreciably be higher. Single level equipment with a proven track record could be bought off the shelf.)

Edit Dec 2018: The FRA has finally updated rules which would allow the T to buy European-spec equipment, like Stadler FLIRTs, which are significantly lighter than an M8 and have better acceleration. Here's a video of a FLIRT accelerating to 100 mph in 72 seconds.

An electric locomotive pulling bilevel coaches would not have the acceleration benefits afforded by EMUs, but it would still be faster, and the cost of an electric locomotive is about the same as a diesel. Both electric locomotives and EMUs have a proven track record, running daily around the world, including on much of the Northeast Corridor.

In the relatively near-term, the T needs to buy new rolling stock. The T's entire single-level fleet dates to before 1990; 55 of the cars were built in the '70s; once the Red Line cars are replaced, they will be the oldest in the system (except, of course, the Mattapan Line). About half of the T's locomotives date to the same time period, with 20 of them dating to 1973. It is no wonder that the agency is constantly short on both cars and motive power.

The T has had little luck buying new diesel equipment: the 40 new locomotives in the fleet are back and forth to the shops on warranty repair, and coaches aren't much better: the Rotem bilevel cars are plagued with problems. So instead of doubling down on diesels that don't work, the T could buy something that does: electric power. Replacing the Providence Line would free up a dozen-or-so train sets, which could be spread across the rest of the system to replace aging diesel equipment there. Thus, the up-front marginal cost of buying new trains would be effectively zero: the T needs to buy new Commuter Rail equipment anyway.

Electric trains are more reliable

Buying electric trains means buying a superior product. While they aren't perfect, electrics have a much better track record of not breaking down. There's no perfect metric for this, as I've mentioned before, since it is based on agency policy, but the numbers are so staggering they're almost hard to believe. The T itself reports that its trains break down approximately every 6,000 miles. Meanwhile, the mostly-electrified Long Island and Metro-North railroads see approximately 200,000 miles between major mechanical failures. (A completely different calculation from Chicago shows similar results: the T is way below its peers.) A more apples-to-apples comparison can be made between different equipment types on the LIRR, where the new electric power breaks down ten times less frequently than diesels. While I'd take some of these numbers with a grain of salt, it's clear that electric-powered railroads are more reliable than diesels.

Another of the costs of running Commuter Rail trains is fueling. Not only does it require staff and fuel, but the trains have to be moved to a fueling location in the middle of the day, which requires additional personnel and operating time and cost. Electric trains carry no fuel, and don't have to make frequent trips to a fueling facility. They also don't have to be plugged in or idled at the end of the day: the power to keep them on and get them started is always flowing above the track.

Electric trains are cheaper to run

In addition to the cost of electricity being less volatile than diesel, electric trains are simply cheaper to operate. This is somewhat less the case in the US, where every multiple unit is treated like a locomotive and subject to more stringent maintenance, but the costs are comparable, if not lower. This is especially the case for shorter train sets; if some trains on the Providence and Stoughton Lines used fewer cars, the costs would be significantly less. A locomotive-hauled train uses basically the same amount of power whether it's pulling four cars or ten. A set of EMUs could easily be broken in half for midday service, reducing operating costs. A study of electrification in Ontario shows annual operation and maintenance savings of 25% (the full study, here, is worth a read). And this assumes low diesel prices. If the cost of oil spikes, electrics pay further dividends.

Electric trains and level-boarding platforms mean faster trips

The fastest trip time for MBTA equipment between Providence and Boston is currently 1:00 (for a 5:30 a.m. outbound trip) with some trips taking as long as 1:14. Amtrak's Acela Regional trains make the trip in 38 minutes (the Acela Express trains make it in 33). Each stop adds about one minute and 45 seconds to the trip, so additional stops at Sharon, Mansfield and the Attleboros would add 7 minutes, for a total of approximately 45 minutes, end-to-end (Alon levy calculates similar numbers). A commuter from Providence would save half an hour every day; from closer-in stations, round trips would be 20 to 25 minutes faster.

High level platforms are just as important (see this post from California for a very similar issue). Today, Commuter Rail trains will spend two or three minutes of time stopped at major stations while hundreds of people climb the steep, narrow steps onto the cars. High level platforms—like those at Route 128, Ruggles, Back Bay and South Station—allow much faster boarding, increasing the average speed and decreasing the amount of crew time necessary to operate a train. They should be added to all stations, but the busy Providence Line stations are a good place to start.

Faster schedules mean more trains

The total amount of rolling stock required for a railroad is based on the peak requirement for rush hour. Currently, most equipment on the Providence Line runs one rush hour trip in the morning, and one rush hour trip in the evening, with some service midday. For some larger train sets, however, these are the only two trips which are run during the day: a large capital expenditure which is only used 10 hours per week. The first train leaving Providence 5:00 a.m. can make it back to Providence in order to run a second trip that gets to Boston around 9:00 (likewise, a 4:00 p.m. departure can be back to South Station by 6:30, after the tail end of the peak of rush hour) but everything else can only run once inbound in the morning and once outbound in the evening. This approximately 2:40 time (based on stopping patterns and layover) is called the "cycle time" of the line, and the amount of equipment needed to run service is based on this.

Now, imagine that you drop that 2:40 cycle time to 2:00 (45 minutes of running time and 15 minutes to turn at each terminal). That 5:00 a.m. train can run a second trip in to Boston at 7:00. (and maybe even a third at 9:00!). This is much more efficient: each train set can provide twice as much service.

To run service every 30 minutes, you only need four trains. Or, with the eight trains currently needed to run rush hour service from Providence, you could run trains twice as often: every 15 minutes. So instead of the current eight departures from Providence (and one short-turn from Attleboro) between 5:00 and 9:00 a.m.—with as much as 50 minutes between trains—you could instead have 16 departures from Providence: one every 15 minutes. This gives you double the capacity (and if trains are 15 minutes faster than today, you may well need it) and walk up service between the two largest cities in the region.

Off-peak, instead of running a train every one to two hours (or longer: there are service gaps of 2:20 in the current schedule), you could have a train every 30 minutes, again, with the same number of trains. (For the Stoughton branch, a short train could shuttle back and forth between Canton Junction and Stoughton during off-peak hours, meeting the mainline trains at Canton.) This is the promise of Regional Rail: fast, frequent, predictable and reliable trains throughout the day. Electrification and high level platforms would allow the T to operate this level of service with no more operating cost than today.

What’s more, much-improved weekend service on the line would also be possible. Today, there are trains only every two or three hours, and on Sundays, basically no service before noon. (This dates back to the days when the New Haven Railroad operated the service and didn’t provide service before noon, ostensibly because the parochial New Haven thought its customers should be in church, not riding the trains.) Hourly weekend service would be possible with just two train sets.

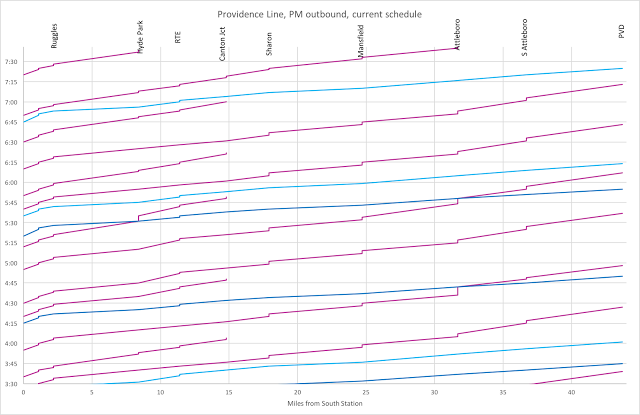

To visualize this, we can use what’s called a “string diagram” of the current MBTA and Amtrak service during the evening rush hour. The morning rush hour is less complex as there are fewer Amtrak trains in the mix since, except for one overnight train, the first Amtrak arrival from New York doesn’t arrive until close to 9 a.m. Each line shows a train running along the line; steeper lines show slower service. Purple lines show Commuter Rail trains, Light blue lines Amtrak regional service, and dark blue lines Acela Express service.

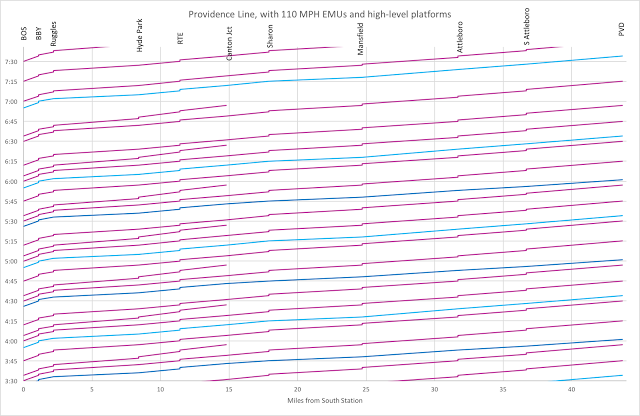

And here's the same diagram, but showing every-15-minute EMU Commuter Rail service:

Electrifying the Providence Line for the MBTA would not be trivial, but the costs would be relatively low given the existing infrastructure, and it provide benefits not just for Providence Line riders but for Amtrak riders and nearby residents. It would allow the diesel equipment on the Providence Line to move to other parts of the system, replacing the oldest equipment elsewhere. It would also be the first step towards building Regional Rail: a rail system which not only takes workers downtown at rush hour, but also provides mobility across the region. And where better to start than between the capital cities of Massachusetts and Rhode Island?

This post will address several of the benefits of upgrading the Providence Line to accommodate fast, electric rolling stock, and how they will allow the MBTA and RIDOT (which subsidizes the portion of the line serving Rhode Island) to increase service, decrease operating costs, and provide a better, more competitive product on the rails. With the MBTA's fleet aging, it's high time to examine the future needs of the network, and to begin the move to electric operation and a Regional Rail system.

Electric trains are cheaper to buy

The MBTA's most recent locomotive procurement had a unit cost of $6 million. The unit cost for the M8s delivered to MetroNorth has been in the range of $2.25 to $2.5 million, about the same as an MBTA Rotem bilevel coach. While the bilevel coaches do have more capacity than the single-level cars, a locomotive and six bilevels has the same capacity and costs the same amount as a train of eight EMUs. (Bilevel EMUs are also an option, although Northeast Corridor-spec'ed bilevel equipment does not yet exist, New Jersey may order some soon. If so, costs may not be appreciably be higher. Single level equipment with a proven track record could be bought off the shelf.)

Edit Dec 2018: The FRA has finally updated rules which would allow the T to buy European-spec equipment, like Stadler FLIRTs, which are significantly lighter than an M8 and have better acceleration. Here's a video of a FLIRT accelerating to 100 mph in 72 seconds.

An electric locomotive pulling bilevel coaches would not have the acceleration benefits afforded by EMUs, but it would still be faster, and the cost of an electric locomotive is about the same as a diesel. Both electric locomotives and EMUs have a proven track record, running daily around the world, including on much of the Northeast Corridor.

In the relatively near-term, the T needs to buy new rolling stock. The T's entire single-level fleet dates to before 1990; 55 of the cars were built in the '70s; once the Red Line cars are replaced, they will be the oldest in the system (except, of course, the Mattapan Line). About half of the T's locomotives date to the same time period, with 20 of them dating to 1973. It is no wonder that the agency is constantly short on both cars and motive power.

The T has had little luck buying new diesel equipment: the 40 new locomotives in the fleet are back and forth to the shops on warranty repair, and coaches aren't much better: the Rotem bilevel cars are plagued with problems. So instead of doubling down on diesels that don't work, the T could buy something that does: electric power. Replacing the Providence Line would free up a dozen-or-so train sets, which could be spread across the rest of the system to replace aging diesel equipment there. Thus, the up-front marginal cost of buying new trains would be effectively zero: the T needs to buy new Commuter Rail equipment anyway.

Electric trains are more reliable

Buying electric trains means buying a superior product. While they aren't perfect, electrics have a much better track record of not breaking down. There's no perfect metric for this, as I've mentioned before, since it is based on agency policy, but the numbers are so staggering they're almost hard to believe. The T itself reports that its trains break down approximately every 6,000 miles. Meanwhile, the mostly-electrified Long Island and Metro-North railroads see approximately 200,000 miles between major mechanical failures. (A completely different calculation from Chicago shows similar results: the T is way below its peers.) A more apples-to-apples comparison can be made between different equipment types on the LIRR, where the new electric power breaks down ten times less frequently than diesels. While I'd take some of these numbers with a grain of salt, it's clear that electric-powered railroads are more reliable than diesels.

Another of the costs of running Commuter Rail trains is fueling. Not only does it require staff and fuel, but the trains have to be moved to a fueling location in the middle of the day, which requires additional personnel and operating time and cost. Electric trains carry no fuel, and don't have to make frequent trips to a fueling facility. They also don't have to be plugged in or idled at the end of the day: the power to keep them on and get them started is always flowing above the track.

Electric trains are cheaper to run

In addition to the cost of electricity being less volatile than diesel, electric trains are simply cheaper to operate. This is somewhat less the case in the US, where every multiple unit is treated like a locomotive and subject to more stringent maintenance, but the costs are comparable, if not lower. This is especially the case for shorter train sets; if some trains on the Providence and Stoughton Lines used fewer cars, the costs would be significantly less. A locomotive-hauled train uses basically the same amount of power whether it's pulling four cars or ten. A set of EMUs could easily be broken in half for midday service, reducing operating costs. A study of electrification in Ontario shows annual operation and maintenance savings of 25% (the full study, here, is worth a read). And this assumes low diesel prices. If the cost of oil spikes, electrics pay further dividends.

Electric trains and level-boarding platforms mean faster trips

The fastest trip time for MBTA equipment between Providence and Boston is currently 1:00 (for a 5:30 a.m. outbound trip) with some trips taking as long as 1:14. Amtrak's Acela Regional trains make the trip in 38 minutes (the Acela Express trains make it in 33). Each stop adds about one minute and 45 seconds to the trip, so additional stops at Sharon, Mansfield and the Attleboros would add 7 minutes, for a total of approximately 45 minutes, end-to-end (Alon levy calculates similar numbers). A commuter from Providence would save half an hour every day; from closer-in stations, round trips would be 20 to 25 minutes faster.

High level platforms are just as important (see this post from California for a very similar issue). Today, Commuter Rail trains will spend two or three minutes of time stopped at major stations while hundreds of people climb the steep, narrow steps onto the cars. High level platforms—like those at Route 128, Ruggles, Back Bay and South Station—allow much faster boarding, increasing the average speed and decreasing the amount of crew time necessary to operate a train. They should be added to all stations, but the busy Providence Line stations are a good place to start.

Faster schedules mean more trains

The total amount of rolling stock required for a railroad is based on the peak requirement for rush hour. Currently, most equipment on the Providence Line runs one rush hour trip in the morning, and one rush hour trip in the evening, with some service midday. For some larger train sets, however, these are the only two trips which are run during the day: a large capital expenditure which is only used 10 hours per week. The first train leaving Providence 5:00 a.m. can make it back to Providence in order to run a second trip that gets to Boston around 9:00 (likewise, a 4:00 p.m. departure can be back to South Station by 6:30, after the tail end of the peak of rush hour) but everything else can only run once inbound in the morning and once outbound in the evening. This approximately 2:40 time (based on stopping patterns and layover) is called the "cycle time" of the line, and the amount of equipment needed to run service is based on this.

Now, imagine that you drop that 2:40 cycle time to 2:00 (45 minutes of running time and 15 minutes to turn at each terminal). That 5:00 a.m. train can run a second trip in to Boston at 7:00. (and maybe even a third at 9:00!). This is much more efficient: each train set can provide twice as much service.

To run service every 30 minutes, you only need four trains. Or, with the eight trains currently needed to run rush hour service from Providence, you could run trains twice as often: every 15 minutes. So instead of the current eight departures from Providence (and one short-turn from Attleboro) between 5:00 and 9:00 a.m.—with as much as 50 minutes between trains—you could instead have 16 departures from Providence: one every 15 minutes. This gives you double the capacity (and if trains are 15 minutes faster than today, you may well need it) and walk up service between the two largest cities in the region.